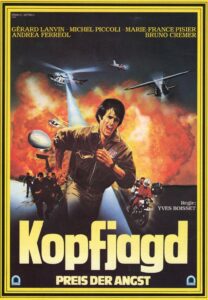

Am 08. März bringen wir um 20:00 Uhr im Cinema Ostertor erneut einen französischen Film auf die große Leinwand. Diesmal geht es in den 80er Jahre, denn wir zeigen Yves Boissets Science-Fiction-Actionfilm KOPFJAGD – PREIS DER ANGST von 1983.

Am 08. März bringen wir um 20:00 Uhr im Cinema Ostertor erneut einen französischen Film auf die große Leinwand. Diesmal geht es in den 80er Jahre, denn wir zeigen Yves Boissets Science-Fiction-Actionfilm KOPFJAGD – PREIS DER ANGST von 1983.

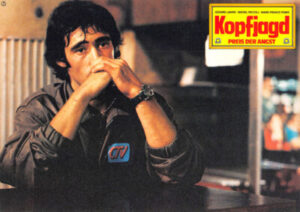

In der nahen Zukunft gibt es eine beliebte Fernsehsendung, die von dem charismatischen Frédéric Mallaire (Michel Piccoli) moderiert wird. An dieser Sendung kann man teilnehmen, indem man entweder als Gejagter um sein Leben rennen muss, oder als Killer versucht den Gejagten zu eliminieren, bevor dieser das Ende der Show erlebt. Um den Millionen-Dollar-Preis zu gewinnen, meldet sich François Jacquemard (Gérard Lanvin) freiwillig als Gejagter für die nächste Ausgabe der Show. Als die Jagd beginnt, entdeckt François, dass die Show manipuliert ist und dass der skrupellose Fernsehsender CTV (unter der Leitung des zynischen CEO Antoine Chirex (Bruno Cremer) und seiner rechten Hand Laurence Ballard (Marie-France Pisier) den Kandidaten tatsächlich hilft, nur um sie am Ende der Show sterben zu lassen und so maximale Einschaltquoten zu gewährleisten.

Wem dieses Szenario bekannt vorkommt: Es basiert auf der Kurzgeschichte „The Prize of Peril“ von Robert Sheckley von 1958. Und dies wurde bereits 1970 als „Das Millionenspiel“ von Tom Toelle und Wolfgang Menge für das deutsche Fernsehen aufbereitet. Ein Kultklassiker. Nach „Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst“ wurde Richard Bachmans (aka Stephen King) Roman „Running Man“ mit Arnold Schwarzenegger verfilmt. Diese Adaption übernahm allerdings sehr viel mehr Elemente aus „Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst“ als aus dem Bachman-Buch, welches allerdings auch von Scheckleys Kurzgeschichte inspiriert ist.

Wem dieses Szenario bekannt vorkommt: Es basiert auf der Kurzgeschichte „The Prize of Peril“ von Robert Sheckley von 1958. Und dies wurde bereits 1970 als „Das Millionenspiel“ von Tom Toelle und Wolfgang Menge für das deutsche Fernsehen aufbereitet. Ein Kultklassiker. Nach „Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst“ wurde Richard Bachmans (aka Stephen King) Roman „Running Man“ mit Arnold Schwarzenegger verfilmt. Diese Adaption übernahm allerdings sehr viel mehr Elemente aus „Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst“ als aus dem Bachman-Buch, welches allerdings auch von Scheckleys Kurzgeschichte inspiriert ist.

Regisseur Yves Boisset ist vor allem für seine Polizei- und Gangster-Thriller aus den 1970er Jahren bekannt. Wie beispielsweise „Ein Bulle sieht rot“ oder „Der Richter, den sie Sheriff nannten“. Seine Filme haben oft eine existenzialistische Note und handeln von Einsamkeit des Individuums vor dem Hintergrund eines abstrakten und gleichzeitig unbarmherzig mechanischen Gesellschaftssystems. Somit setzt „Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst“ Boissets Themen konsequent fort.

Regisseur Yves Boisset ist vor allem für seine Polizei- und Gangster-Thriller aus den 1970er Jahren bekannt. Wie beispielsweise „Ein Bulle sieht rot“ oder „Der Richter, den sie Sheriff nannten“. Seine Filme haben oft eine existenzialistische Note und handeln von Einsamkeit des Individuums vor dem Hintergrund eines abstrakten und gleichzeitig unbarmherzig mechanischen Gesellschaftssystems. Somit setzt „Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst“ Boissets Themen konsequent fort.

„Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst übersetzt die zentralen Themen des Regisseurs – politische Paranoia und die Hilflosigkeit des Einzelnen angesichts allgegenwärtiger Korruption – in ein neues audiovisuelles Register.“ – critic.de

„Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst übersetzt die zentralen Themen des Regisseurs – politische Paranoia und die Hilflosigkeit des Einzelnen angesichts allgegenwärtiger Korruption – in ein neues audiovisuelles Register.“ – critic.de

„Eine überaus gelungene Mischung aus zynischer Medien-Satire und knackigem Genre-Reißer, den man getrost als den besseren Running Man betrachten kann.“ – moviebreak.de

„Das Doppelbödige an „Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst“ ist die Meta-Ebene, da uns der Film zum Bestandteil des Publikums macht und wir Filmguckerinnen und -gucker uns unseren Voyeurismus eingestehen müssen (auch wenn wir Realität und Fiktion natürlich unterscheiden können – aber wie lange noch?).“ – Die Nacht der lebenden Texte

„Das Doppelbödige an „Kopfjagd – Preis der Angst“ ist die Meta-Ebene, da uns der Film zum Bestandteil des Publikums macht und wir Filmguckerinnen und -gucker uns unseren Voyeurismus eingestehen müssen (auch wenn wir Realität und Fiktion natürlich unterscheiden können – aber wie lange noch?).“ – Die Nacht der lebenden Texte

Wir zeigen den Film im französischen Original mit deutschen Untertiteln und einer Einführung.